It's early January 2002, we're on our first trip to South America, visiting Alison, my sister and her family. We've been to the Sacred Valley and the many Quechua / Inca sights. On the classic historical, cultural Peruvian route. Returned to Lima and headed south to Paracas for a few days on the coast, away from the Lima fog and smog belt. We'd been out to the islands to visit the colony of Inca Terns and the sea lions, sailed past the Candelabra geoglyph, then on the second day, had driven out into the desert and the terra firma element of the national park.

Somewhere on one of those headlands, where the sand desert suddenly collapses into the ocean, we both independently turned to each other and admitted: "I want to be on my bike out here". Forget any elemental romanticism, the northern Atacama is too stark and severe for that. It's an uncomplicated landscape, the bones of it's geography are set naked and uncompromised.

And now we've returned again. Only it's a very different place. Gone is the hotel we stayed in, gone is 'The Cathedral', gone most of the town.

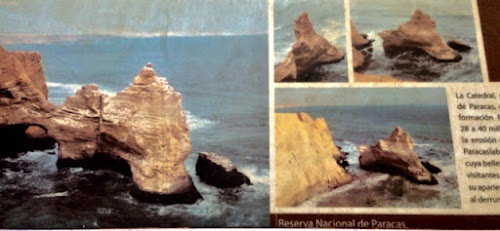

Pisco has the unenviable distinction of being the world's most unstable, 'quake prone city. It can be of no coincidence that it's patron is the 'Señor de la Agonia', for it sits on the edge of a tectonic plate that suddenly moved in 2007, resulting in a major earthquake. The shake not only destroyed the greater part of the city's infrastructure, it also removed one of the national park's iconic structures. "The Cathedral", was a geo-arch that is now rendered to a sea stack. A tooth of sandstone eroding under the relentless battering of the ocean.

Today there is little evidence of the 'quake. The original church, Cathedral de San Clemente in the plaza is now a freshly painted, partial ruin, one of it's spiral turrets swinging by a thread of re-bar, the cupola part-broken like an empty eggshell. You can still look through the broken window panes to the dust encrusted pews, the altar lost in the farthest gloom. The bings of rubble that at one time scarred the coastal road are now all cleared away; gone too are the heaps of builder's sand and cement outside homes that we slalom'd around on our visit last year.

For a denizen of a geologically stable country, it's voyeurism. To watch the human tenacity for revival, to try to imagine the mindset that lets you rebuild, to fight the knowledge and the possibility of another seismic convulsion from nature. The new church has arisen beside the edifice of the old, our old hotel has moved considerably upmarket and shrouded itself behind a high fence. 'The Cathedral' now but a stump, a memory on the storyboard that over looks the event. Only to get to that point you need to cross a giant crack in the earth. It takes little imagination to realise that this piece of desertscape will be the next sacrifice to the ocean.

It's late October 2015, and we've returned again to where it all began. To the start of the wanderlust. Still the place has that same magic that captivated me, despite my many years, my many experiences, my many lives that lie in between.